Cricket is a supposedly numbers-heavy sport, but it’s curious and peculiar in the way that recorded statistics capture only the results of each ball. A dismissal is only recorded if a catch goes to hand or the stumps are broken; nothing is recorded when the batter is beaten. This is a hindrance to a proper […]

Cricket is a supposedly numbers-heavy sport, but it’s curious and peculiar in the way that recorded statistics capture only the results of each ball. A dismissal is only recorded if a catch goes to hand or the stumps are broken; nothing is recorded when the batter is beaten. This is a hindrance to a proper to description of the game, since results depend on a multitude of factors, including luck. Cricketers strive on the field to execute their craft as best as they can to create as many chances as they can. Whether those chances go to hand, or go in the scorebook, is not completely controllable.

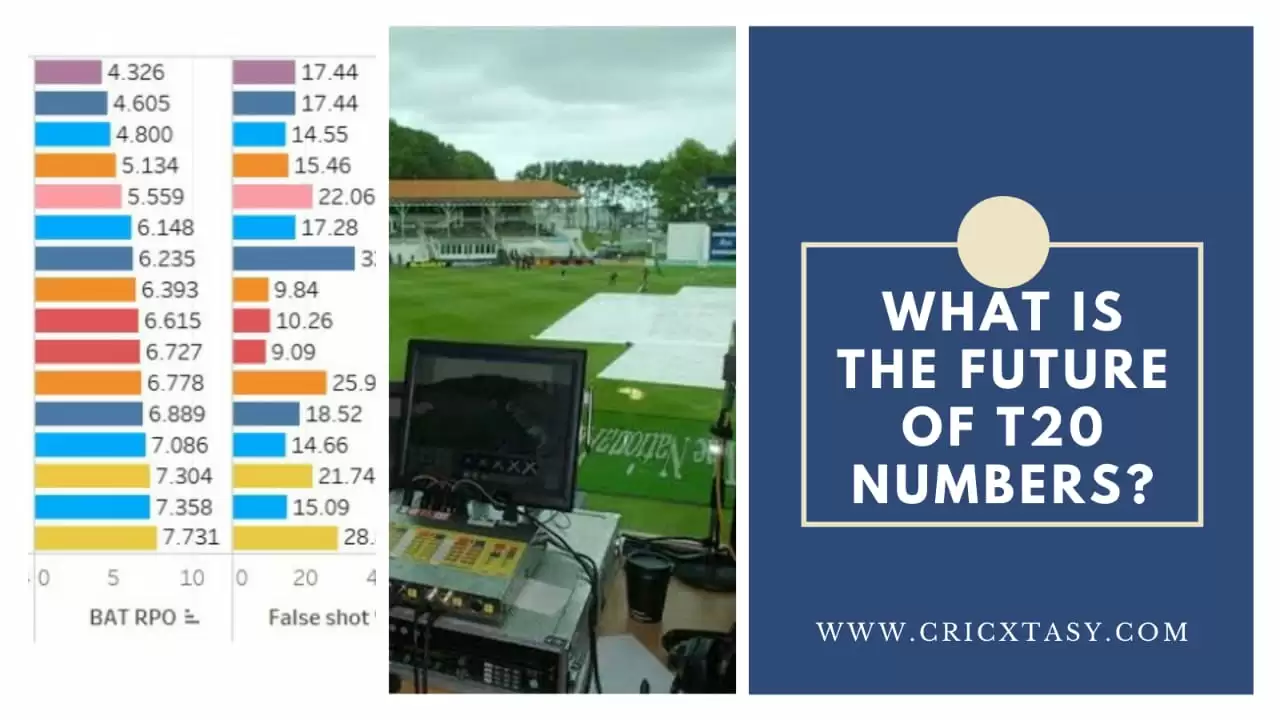

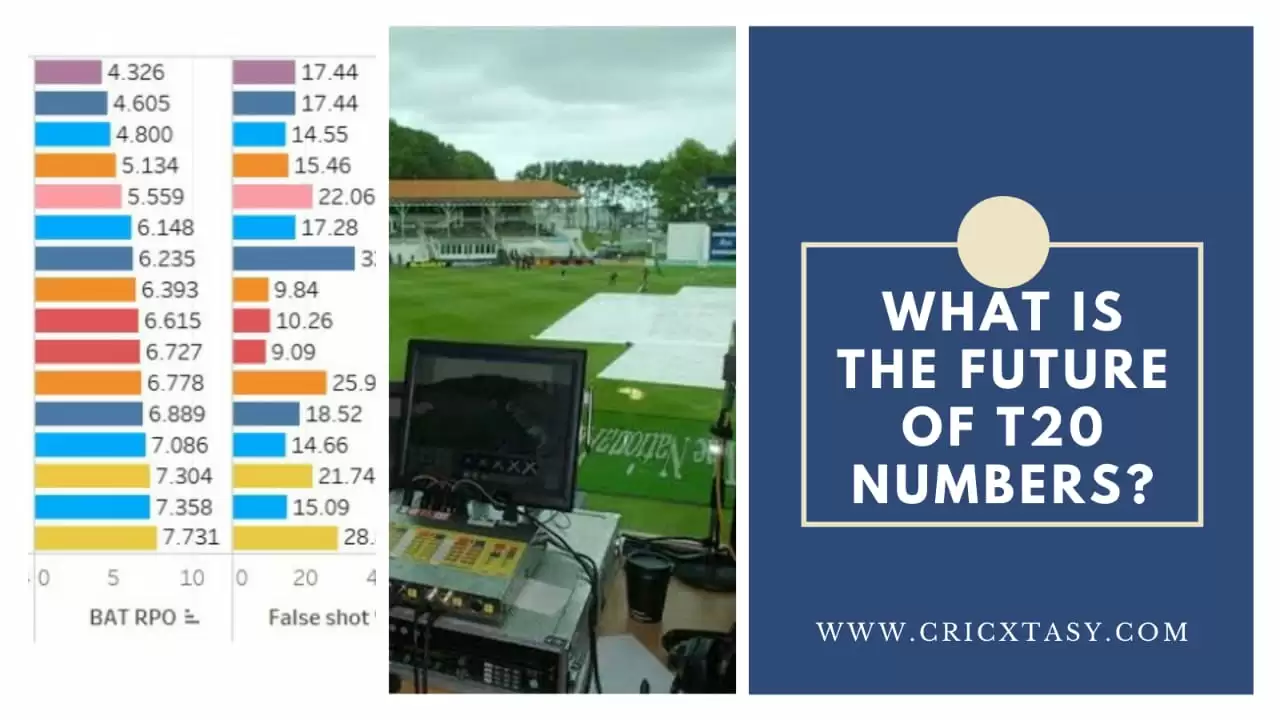

And thus, a measure of chances created (for bowlers) or defence/shots attempted (for batters) is a more accurate descriptor of the game, which actually attempts to describe what the players did on the field, rather than what the players’ actions resulted in. The latter is a clearer indicator of ability over the kind of sample sizes cricket has. Unfortunately, cricket is conditioned to talk in terms of result statistics, and barring Cricinfo’s control percentage, and the random drip of nuggets from the CricViz handles, such stats are almost never in the public domain.

I often ask myself why cricket “analytics” has suddenly skyrocketed in popularity in the recent years. The easier availability of data in the public domain through Cricmetric and Cricsheet has had a major role to play, but taking a broader view, the demand for analytics beyond archaic cricket numbers comes from the blossoming of franchise T20, which demands that players be quantified better; there is value attached to their performance, and real consequences of how well franchises can purchase personnel. Also, conventional metrics are inept at describing T20. Neither of these factors was relevant in an age when ODI and Test cricket between countries (that are not teams made in “free” markets) dominated the landscape.

I think “impact” style numbers in T20 are pretty well-established now. This kind of metric compares a player’s output with the average player’s output in the same “situation”. The quality of your metric depends on how well you can define your “situation”, by taking various levels of context into account. This is the basis of Cricketingview’s Misbah/Jogi measures, my own runs-above-average metric, and also of Cricviz’s Impact calculation. We now need to move ahead of these and look to numbers like “boundaries attempted” and “outcomes when the ball is attacked”, which is in line with the philosophy of measuring the ability to execute a skill, rather than capturing the final outcome of a delivery.

The day is not far when T20 will need further specialisation. A “middle-overs enforcer” might be needed to bowl hard lengths at high speeds, a death specialist might be needed to bowl wide yorkers. It is suboptimal to judge them on their numbers, even after accounting for context. Instead, analysts should measure the ability to bowl that hard length, or bowl that wide yorker, and judge players on the efficiency of execution. This view analyses cricketers on the basis of purely how well they can ply their (limited) set of skills, isolating it from the recorded result. Such metrics are then directly relevant to designing strategy on and off the field. The question asked is: “How well is the player executing this skill, regardless of result?”

Small sample sizes, as ever, thwart the inferential power of cricket stats, but barring that, the two open questions in cricket, in my mind, are:

Currently recorded cricket stats are the highest level of record, in that they give descriptions most removed from the actual game. At a lower level, closer to the game, is detailed ball-by-ball tracking data, which enables us to measure attempts like I’ve mentioned before. At an even lower level, we have a fundamental description of the physical dynamics of cricket: biomechanical data. Recorded data tells you what happened, tracking data tells you how it happened on the pitch, but biomechanical data goes a step further to describe what the player did to make it happen on the pitch. Analysing and using biomechanical data is your best bet to increase the efficacy of players at executing specific skills. And that’s why I feel it’s the next step in cricket data.

The current times have seen an uptick in hobbyists doing great video analyses online. In addition, cricket Twitter has been abuzz with talk of biomechanics, of both fast bowling and hitting. While the footage available to common fans has been used brilliantly by amateur analysts, teams should be looking to extract a wealth of data from nets and practice sessions. Imagine installing markers on a batter and making them hit a certain shot 200 times against a certain kind of delivery. Then, combining this with biomechanical research on optimising the body’s dynamics for the best power hitting to make precise modifications to the batter’s movements. Some will say this robs the game of romance, but I say it will make for better cricket in the long run. In the next decade, high-res video cameras, tracking technology and increased research will act in concert to make biomechanical / detailed video analysis the centre of cricket analytics. This is of course going to be in addition to better models for measuring performance using just numbers, which should move in the direction of measuring attempts.