A low-down on the differing batting strategies used by India and New Zealand against swing

Kane Williamson arches forward. The ball drifts into the pitch like a seagull plunging into the ocean to capture its prey and bounces back. But as it begins its post-bounce trajectory, the ball swerves. It hits the leather, and alters its behaviour, like an old man who has a raw nerve that has been touched. But Williamson’s bat path is not carved yet. The bat brandishes as though it had never been up, the ball strikes its middle, and as if he has touched fire, Williamson withdraws his bat. No posing for photo, no post-contact path correction.

More than a hundred miles south, Virat Kohli’s bat is in motion. Kohli and Williamson are at the vanguard of their teams’ batting production lines against swing. One of these productions is extremely successful, the other less so. Watching Williamson and Kohli tough it out in swing-friendly conditions against elite attacks on side-by-side screens presents us with the rare opportunity to both taste the dish and dissect the recipe at the same time. And so, dissect we did.

The caveat here is that this article remains theory, not fact. Feynman once said, “The principle of science, the definition almost, is the following: The test of all knowledge is experiment. Experiment is the sole judge of scientific ‘truth’”. This article will do nothing of the sort. Biomechanical data pertaining to sporting matches is still light years away from our hold, and using the scant publicly available ball-tracking data (thanks mostly due to CricViz) floating around on Twitter means that we risk being out-of-date. Such data we shall cite when feasible, but understand this anatomy for what it is.

New Zealand and India’s blueprints versus swing differ in at least five ways.

The first of these is universally acknowledged. The New Zealand batters “adjust” versus swing, the Indians “smother” swing.[1] This is reflected in their interception points, and epitomized by Williamson and Kohli: only Steve Smith and Rory Burns meet the ball later than Williamson,[2] while Kohli bats one Jamieson away from the stumps (interception point 2.3 m as of June 2021).[3] And while team-by-team statistics remain unattainable, the mind recalls Rishabh Pant,[4] Rohit Sharma and Shubman Gill[5] playing copycat during India’s tour to England. Tom Latham and Henry Nicholls never have.[6]

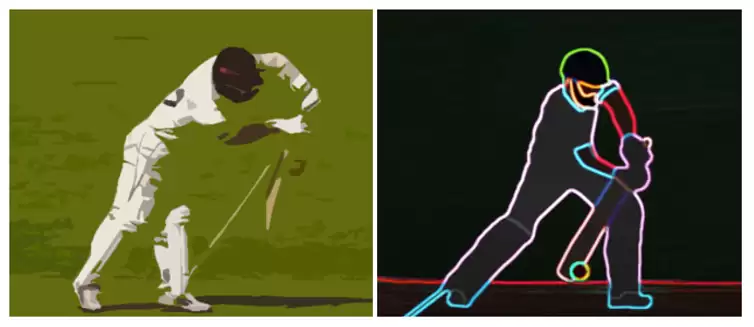

A late interception point could be touched off by two things. One, standing inside the crease. Two, connecting the ball underneath the eyeline. As far as we can tell from the above exhibit, in New Zealand’s case it seems to be driven mainly by the former. Similarly, the Indians’ early interception points are guided by both batting outside the crease and taking giant forward strides to the ball – a reflection of a lifetime spent smothering spin, a task vitally important for vanquishing slow bowling.[7] Which of these is the better strategy is contentious, but we do know that smothering returns marginally higher upshots than adjusting versus spin.[8]

The second prong of their arsenal against swing is their attacking philosophy. The Indians launch their combat knives at all half-volleys, the Kiwis rein themselves in against half-volleys outside the offstump. Instead, they pull “good” lines and lengths in front of square, a skill considered important for batting success in Australia.[9] The reason is probably situational. The professionalization of cricket in New Zealand forged a players’ association, and the players’ association pushed the NZC to issue a “warrant of fitness” that all grounds fit for hosting organized cricket must fulfil. Subsequently, batting averages have gone through the roof.[10] Today there is swing, but it does not dominate seam.

In cricket, the fuller the ball the more it swings, the shorter the ball the greater it seams.[11] But in India, it never swings. Optimizing your batting against pace in Indian conditions entails optimizing it against seam, and half-volleys do not seam. So, Indians drive through the line.

On the contrary, optimizing batting against the full length in New Zealand involves optimizing it against swing, while optimizing it against the good length demands optimizing it against seam and swing. The half-volley that courses through like a speedboat in India wobbles like a speedboat’s trail in New Zealand – so the risk of attacking it looms larger. While at the same time, a horizontal-bat shot effectively eliminates unforeseen seam from “good” balls. This horizontal-bat shot is the pull, a heave used well against the good and short lengths. In sum, New Zealanders don’t cover drive, but they pull prodigiously.

If attacking choice diverges, then so must attacking technique. Rich Hudson, author of “Perform Beyond Pressure: The Keys to Realizing Your Potential” and ECB Level-4 coach, knows a thing or two about batting technique. One such thing is that the best Australian batters display two traits in abundance while punishing half-volleys: high backlift, and a side-on shoulder alignment at the highest point of the upswing. Not surprisingly, English batters demonstrate the opposite values.[12]

The reason is probably similar. The chief raider in Australian conditions is seam, and front-foot attacking strokes are played against balls which do not seam. So, early shot initiation and side-on alignment. This does not hold true of swinging venues, where the fuller the ball the later the shot be initiated. India and Australia are similar in one respect: pace bowling is seam bowling. Although not to the same extent, Hudson’s distinction applies to Indian and New Zealand batters too.

Henry Nicholls, Colin de Grandhomme, Williamson, Latham, and Ross Taylor were the best Kiwi players of swing between 2018 and 2020.[13] With the possible exception of Latham (second from top right), all four others display a considerably low backlift at the highest point of upswing while attacking through the front foot. Along the other end of the spectrum are the Indians – Rohit Sharma, Shubman Gill, Kohli, Rishabh Pant, and Hanuma Vihari (left to right) – who commence the shot with the bat stationed well above their helmets. The difference is that in the Kiwi homestead the half-volley swings, in the Indian shack it does not.

Two minor nuggets remain unplumbed. While swing is king in England, the dichotomy that unravels most persistently in contests between Asian and non-Asian sides is the spin game. How do Indian and New Zealand batters stalk up against each other here? Conceivably, the Indians stretch forward more and bend their backs more while defending. But more seethes under the surface than meets the eye.

The divergence is two-fold. The first point is that the Kiwi batters sweep fewer balls. The Indians have taken recent flak for being reluctant sweepers, but Nathan Leamon and Ben Jones’ “Hitting Against the Spin” highlights that a marginally higher proportion of balls from spinners gets swept in India than in New Zealand – 3.5% to 3.0% – a consequence of lower bounce in Asia which makes the sweep handier, and inflation of offspinners. The argument is that since off-spin bowlers turn the ball into the right-hander, they land fewer LBWs: the ball is almost always striking the pads outside off-stump or meandering past leg-stump. While against left-arm finger-spinners, this theorem fails to hold.

New Zealand produces approximately 10% more left-arm spinners than India, the bulk, we may reasonably assume, being finger-spinners. To sweep them is a fallible use of resources, and batters reared on home turfs display features ideally suited to those home pitches. The implication is that Daryl Mitchell’s dazzling array of sweeps and reverse sweeps that dismantled Jack Leach in Birmingham were more likely the anomaly rather than the mean.

Lastly, there is something of a ballpark. It seems to be the case that when they loft spin the Indians like to swing their backsides off while the New Zealanders cling to control. The Kiwi hoist resembles an exercise in abstinence, played without a prolonged upswing or break neck bat speed or flourishing follow through. The intent is to nudge the ball to the outfield rather than show it to outer space. The underlying cause is less apparent, but maybe New Zealand’s high-bounce surfaces bring catching fielders more into action, and simultaneously the defensive techniques of its batters are less faultless. And so perhaps an attacking strategy gets converted into a defensive recourse.

These five choices separate the Indians from the Kiwis, but there is little evidence to suggest that one of these is better than the other. For starters, we may be way off. Biomechanical data is required to confirm at least three of these hypotheses, and we are farther away from that in the sporting industry than Kohli fishes away from his off-stump. What we know with certainty is that the Indians contact the ball early in its trajectory, and have attacking techniques that may be well-suited to Australian conditions. But when Kohli and Williamson wield their quills in unfamiliar terrains on adjacent screens, few things seem more urgent than to document their calligraphy for posterity. And so, document we did.