Jasprit Bumrah ended with figures of 5/83 in the first innings of the first Test.

In a country in which the first instinct of a five-year-old is to pick up a bat, greatness with the ball in hand is a rare sight, more so if you are a fast bowler. In comes Jasprit Bumrah, almost walking through his run-up and defying all odds. The bowling style, unique. The load, like the hands of a clock. The release is like he’s having a conversation with the pitch. And a follow-through that exhibits aura. No words. No banter. Pure artistry.

Bumrah’s bowling action is nowhere close to what an ideal action for a fast bowler should be. His action was questioned in his early days, but his childhood coach Kishore Trivedi backed him to keep his action the same. And we may say that the rest is history. Bumrah, at the top of his mark, is an event waiting to unfold. And for the Indians, Bumrah at the top of his mark is hope.

Making a comeback from injury, India’s prime speedster managed to pick up another five-wicket haul in the first innings of the ongoing Test in Leeds. Bowling almost 25 overs at an economy of 3.36, Bumrah made the English batters toil hard for each run. Mind you, he’s landed five wickets after three catches were put down off his bowling. Unlike every other bowler’s reaction to the dropped chances, not a single word came out from his mouth in the form of a reaction. He just walked into the Press Conference. “Catches aren’t dropped by anyone on purpose. It is part and parcel of the game, and people do learn from their experiences”, is all he had to say.

The 31-year-old has a knack for assessing conditions to perfection. Be it a lush green top, a wicket on which the ball is seaming around, or a wicket which has nothing in it for the pacers. Bumrah’s ability to get into the batter’s mind is second to none. It seems as if he can predict what the batter is going to do, and exactly bowl according to that. From setting up Keaton Jennings right in front of the wicket in 2018, to the toe crusher last year, which had Ollie Pope’s name all over it, his brilliance has ceased to go unnoticed.

As mentioned earlier, Bumrah’s bowling action is nothing like what an ideal bowling action for a fast bowler should be. Let us try to decode every aspect of his bowling action to understand the dynamics of his workload.

The secret of Bumrah’s run-up is that there’s no run-up. It is almost a walk to create momentum before release. If you watch him at the top of his mark, he starts in a very simple manner. His hands are placed as if he is giving himself a first pump. No arms brushing against the waist. Nothing orthodox. The orthodox purpose of running with hands brushing one’s waist is to cut through the air and create momentum, which eventually helps a smooth release. But in Bumrah’s case, orthodox isn’t a thing. He increases the intensity of his right foot in his run-up, allowing him to generate momentum before release.

Jasprit Bumrah loads the ball in a very unique way. His hands almost look like the hands of a clock, indicating the time – 11:15. What’s more special and unique about the way he loads is the fact that his arms never fold, till only the bowling arm does a bit at the time of release. Again, the fast bowling textbook requires a bowler to load with his bowling arm close to his chest, something which bowlers like Brett Lee and Dale Steyn used to execute perfectly. Only if Bumrah played by the textbook. The ball in his hand points towards mid-off at the time of his jump, which is again very different to what it should ideally be. The Indian speedster’s action is just a blend of unique execution skills, which tends to work in his favour to create momentum. It is just like a combination of colours thrown randomly on a canvas, still creating a masterpiece!

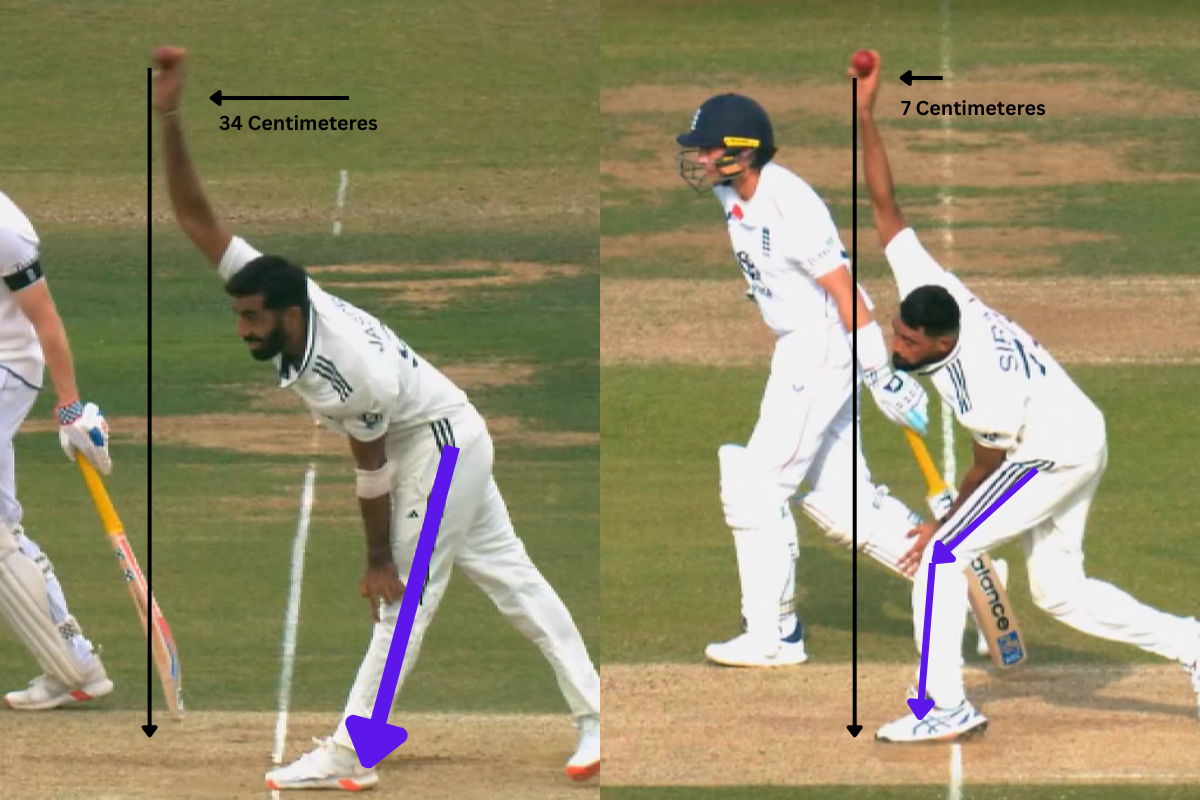

Now comes the most important bit. This is the point where Bumrah creates his unique selling proposition (USP). Coming out of business terms, the release is the point where Bumrah separates himself from the rest. If you look at his point of release, in comparison to the release of Mohammed Siraj, in this case, you will notice some differences. Bumrah’s release point is 34 centimetres (approximately) from the popping crease, as compared to Siraj’s seven centimetres. This is where the former tends to hurry the batter, and creates an edge which allows him to rattle his nemesis. The ball being released from almost 27 centimetres ahead of the popping crease in comparison to other bowlers means that it will hurry on to the batter, come a lot quicker and pose immense problems if it swings or seams. In other words, the pitch is 27 centimetres shorter for the batter, giving him less time to react.

There’s another point which we need to look at. Bumrah’s action does not allow him to bend his knees while he releases the ball, unlike Siraj in this case. Almost all fast bowlers tend to bend their left knees (for a right-arm fast bowler) at the point of release to create an angle. This helps them to decrease the load on their back at the time of release. In Bumrah’s case, his leg doesn’t create that angle, due to which he is more upright in comparison to others. This, in turn, increases the stress on his back, which could have led to complications in his injury recently.

The follow-through is one of the most important aspects of fast bowling. It is an end to the bowler’s run-up, an end to a poetry in motion. In the absence of a follow-through, fast bowlers would immediately stall after their release, creating humongous pressure on their bodies. A follow-through helps the bowler slowly decrease his speed before coming to a halt. Now, if there’s so much of a difference in the run-up, the load and the release, there’s no way Bumrah is following the textbook in terms of his follow-through. For an orthodox fast bowler, the bowling arm ends up beside the left leg (for a right-arm fast bowler). But in Bumrah’s case, his bowling arm ends up between his legs. This is because of the angle at which his arms stack up during release. The bowling arm comes down at a particular angle, making it difficult for it to end up beside his left leg.

Being a fast bowler doesn’t come without its repercussions. Every single delivery bowled puts the lumbar spine under tremendous pressure. Generating pace is a risky affair. Not every injury can be avoided, but in today’s day and age, with cricket becoming fast-paced, even the best workload managers can incur injuries. Workload management is a science behind determining how many overs a bowler bowls, and at what intensity. It is more of a science that takes a bowler’s fatigue or tiredness into account. Hence, it is of utmost importance to communicate to avoid injuries.

Bumrah isn’t the only case of a back injury in Indian cricket. The likes of Varun Aaron and Mayank Yadav are other examples. While Mayank Yadav’s pace drew everyone’s attention, it didn’t come with consequences. As Ian Pont, head coach and founder of the National Fast Bowling Academy in the United Kingdom, puts it, “workload management is about protecting the bowler from the game, not the game from the bowler.”

ALSO READ:

With that bowling action, there is a huge stress on the body. Couple that with the increasing number of games being played all over the world. It is hence no surprise that Jasprit Bumrah has decided to play in just three of the five Tests in England.

Stats aren’t everything. Stats, without context, are like an ocean without water. Bumrah’s bowling isn’t just about taking wickets or the number of wickets he has taken. What he has managed in a decade of his career is the belief he plants in the minds of fans when he is at the top of his run-up. It is about his captain turning to him every time the team needs a breakthrough. It is the hope, more than the wickets. Good bowlers talk to the batters. Great bowlers talk to the ball. And Bumrah, if not yet, is surely very close to becoming the latter. And maybe, just maybe, the nation will again want time to stop when Bumrah exhibits his class.